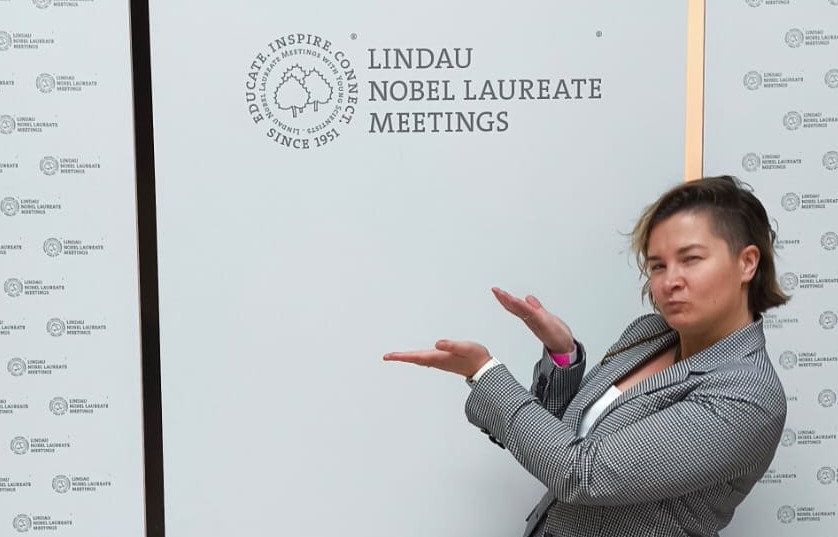

Some thoughts from the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting 2024

That once in a lifetime when you can ask a ton of questions to Nobel Prize winners!

An unexpected meeting

The meeting in Lindau played the role of a small personal earthquake for me and changed the way I look at academia and science. I expected scientifically interesting lectures on different physics topics, as well as excessive glorification of the past and how it “used to be”. Instead, from the stage where the Nobel Prize winners presented, there flowed a huge amount of motivation and understanding of our daily challenges and joy in how academia is changing (and frustration that it is changing too slowly). However, the most inspiring thing was meeting the Nobel Prize winners, who (unfortunately? fortunately?) are just people in love with science, while I expected beings with supernatural powers.

Disruptive science means your colleagues will say you’re crazy

The most motivating observation from the meeting was the common denominator of the Nobel Prize winners’ memories when they talked about choosing the scientific topics that ultimately led them to the award. Almost every one of them encountered disbelief and doubt from the academic community at the beginning of their journey. Some (like Alain Aspect, Serge Haroche, and Anton Zeilinger) mentioned that renowned professors (like Richard Feynman) ridiculed their chosen research topic or anxiously asked if they already had permanent positions to do such crazy research. When at breakfast with Haroche and Zeilinger, I joked that it was then a good sign when people said your research was crazy, Anton Zeilinger clarified that although it may be a good sign, unfortunately, these people can also be right! I will remember this when Reviewer 2 writes that my research results are “secondary and obvious and certainly wrong” (can they even be both?!) because their intuition says so 😉

Wisdom from nobelists

In other interesting discussions, Steven Chu said that he works best with one postdoc and one PhD student when he can still do the research himself. This poses an interesting contrast to the current profile of research groups of renowned professors (at least in quantum physics), where groups can reach fifty people. In addition, he gave us a “simple” recipe for the Nobel Prize – if you make a new research instrument, you have a good chance of observing something groundbreaking because you are the first person to “look under the rock”! It was also interesting that some professors were clearly tired of the commotion that engulfed their lives after winning the Nobel Prize, and all they wanted was to continue their scientific work in peace. Others got involved in politics, but they said that the power that the prize gives is partly illusory. Yes, politicians want to take a picture with you, but after the conversation, they forget about the advice and recommendations. All the Nobel laureates were also extremely supportive, even though the whole event must have been tiring for them. Wherever they appeared, they were surrounded by groups of young scientists. That is why I really appreciated the additional events that allowed me to meet the Nobel laureates in more controlled conditions and more intimate groups.

Difficult questions without answers

I don’t feel confident writing this paragraph, but I also wanted to mention a certain disappointment resulting from my exaggerated expectations towards Nobel Prize winners. I expected them to have all the answers to the challenges of academia and ideas on how to fix them. How to resist the prestige of publishing in Nature and Science, which, feeding on the free work of scientists, grow into financial giants? What should be the mechanisms for observing professors who change over time under the influence of power (as scientific research clearly indicates: power changes everyone, i.a., reducing their empathy) and can get detached, forgetting the needs and struggles of young scientists? How to cope with the fact that as group leaders, we are responsible for the mental health and scientific success of our group members, but we lack training? These are just examples of many persistent challenges, but the professors I asked answered with, “it’s a difficult problem that is worth solving”.

Increased personal visibility

Another very exciting event for me was giving a lecture as part of the “Next Gen Science” panel devoted to artificial intelligence and physics. There, I presented our proposal to automate the search for schemes for laser cooling of atoms and molecules. It seemed unrealistic to me – I had talked about my work on laser cooling to over 600 brilliant young scientists and a number of Nobel Prize winners, some of whom received their awards for… laser cooling. The organizing committee of the Lindau meeting also took care of increasing the visibility of the young scientists themselves. Thanks to my participation in the meeting, I gave an interview to the “Women in Research” blog, and also to a German newspaper, which reported on selected presentations by young scientists.

Thank you, FNP!

To sum up, this extraordinary event gave me a lot to think about, inspired me, and gave me additional motivation to fight the oddities of academia. If it weren’t for the Foundation for Polish Science, this would never have happened, and I am extremely grateful to them. I plan to repay them by taking everything I have learned here and using it to make academia a better, more friendly, and diverse place! Keep your fingers crossed! 😉

“Science and democracy go together” by Saul Perlmutter

“Give up all classical ideas about quantum physics” by Anton Zeilinger

“German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer, who studied requirements and conditions for mutual understanding, suggested that a good conversation presupposes that the other person could be right.” by Countess Bettina Bernadotte

“Truth is that that is revealed by the scientific method, observation, experiment, and theory. It’s always tentative, must be subjective to tests, and Nature is the only judge. We can never be sure that we are definitely right, we can only be sure when we are wrong. (…) We are surrounded by liars and fabricators, many of our leaders, politicians, and now LLMs as well, who are trained to come up with something that sounds good but might not be true. (…) How are we to compete with liars (…)? How are we to convey (…) to the innumerate society that many ‘facts’, theories, predictions, having passed through the strong filters of the scientific method, are indeed reliable, while at the same time, and this is the real difficulty, retaining the uncertainty and tentativeness that scientific method produces?” by David Gross.

Please see his lecture on scientific truth! It’s here!